Continuing the theme of alternative approaches to teaching calculus, I take the liberty of posting a letter sent by Donald Knuth to to the Notices of the American Mathematical Society in March, 1998 (TeX file).

Professor Anthony W. Knapp

P O Box 333

East Setauket, NY 11733

Dear editor,

I am pleased to see so much serious attention being given to improvements in the way calculus has traditionally been taught, but I’m surprised that nobody has been discussing the kinds of changes that I personally believe would be most valuable. If I were responsible for teaching calculus to college undergraduates and advanced high school students today, and if I had the opportunity to deviate from the existing textbooks, I would certainly make major changes by emphasizing several notational improvements that advanced mathematicians have been using for more than a hundred years.

The most important of these changes would be to introduce the notation and related ideas at an early stage. This notation, first used by Bachmann in 1894 and later popularized by Landau, has the great virtue that it makes calculations simpler, so it simplifies many parts of the subject, yet it is highly intuitive and easily learned. The key idea is to be able to deal with quantities that are only partly specified, and to use them in the midst of formulas.

I would begin my ideal calculus course by introducing a simpler “ notation,” which means “absolutely at most.” For example,

stands for a quantity whose absolute value is less than or equal to

. This notation has a natural connection with decimal numbers: Saying that

is approximately

is equivalent to saying that

. Students will easily discover how to calculatewith

:

I would of course explain that the equality sign is not symmetric with respect to such notations; we have and

but not

, nor can we say that

. We can, however, say that

. As de Bruijn points out in [1, 1.2], mathematicians customarily use the

sign as they use the word “is” in English: Aristotle is a man, but a man isn’t necessarily Aristotle.

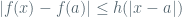

The notation applies to variable quantities as well as to constant ones. For example,

if

and

if

Once students have caught on to the idea of notation, they are ready for

notation, which is even less specific. In its simplest form,

stands for something that is

for some constant

, but we don’t say what

is. We also define side conditions on the variables that appear in the formulas. For example, if

is a positive integer we can say that any quadratic polynomial in

is

. If

is sufficiently large, we can deduce that

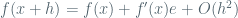

I would define the derivative by first defining what might be called a “strong derivative”: The function has a strong derivative

at point

if

whenever is sufficiently small. The vast majority of all functions that arise in practical work have strong derivatives, so I believe this definition best captures the intuition I want students to have about derivatives. We see immediately, for example, that if

we have

so the derivative of is

. And if the derivative of

is

, we have

hence the derivative of is

and we find by induction that

Similarly if and

have strong derivatives

and

, we readily find

and this gives the strong derivative of the product. The chain rule

also follows when has a strong derivative at point

and

has a strong derivative at

.

Once it is known that integration is the inverse of differentiation and related to the area under a curve, we can observe, for example, that if and

both have strong derivatives at

, then

I’m sure it would be a pleasure for both students and teacher if calculus were taught in this way. The extra time needed to introduce notation is amply repaid by the simplifications that occur later. In fact, there probably will be time to introduce the “

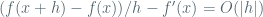

notation,” which is equivalent to the taking of limits, and to give the general definition of a not-necessarily-strong derivative:

The function is continuous at

if

and so on. But I would not mind leaving a full exploration of such things to a more advanced course, when it will easily be picked up by anyone who has learned the basics with alone. Indeed, I have not needed to use “

” in 2200 pages of The Art of Computer Programming, although many techniques of advanced calculus are applied throughout those books to a great variety of problems.

Students will be motivated to use notation for two important reasons. First, it significantly simplifies calculations because it allows us to be sloppy — but in a satisfactorily controlled way. Second, it appears in the power series calculations of symbolic algebra systems like Maple and Mathematica, which today’s students will surely be using.

For more than 20 years I have dreamed of writing a calculus text entitled O Calculus, in which the subject would be taught along the lines sketched above. More pressing projects, such as the development of the TeX system, have made that impossible, although I did try to write a good introduction to notation for post-calculus students in [2, Chapter 9].

Perhaps my ideas are preposterous, but I’m hoping that this letter will catch the attention of people who are much more capable than I of writing calculus texts for the new millennium. And I hope that some of these

now-classical ideas will prove to be at least half as fruitful for students of the next generation as they have been for me.

Sincerely,

Donald E. Knuth

Professor

[1] N. G. de Bruijn, Asymptotic Methods in Analysis (Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1958).

[2] R. L. Graham, D. E. Knuth, and O. Patashnik, Concrete Mathematics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1989).

Sorry, I forgot to activate the comments. It is fixed now. Your comments are welcome!

By: Alexandre Borovik on April 14, 2008

at 3:20 pm

Very interesting article. Also, since I’m the first to comment I thought I’d mention you’ve hit the front page of Reddit! Congrats!

By: Ben Gotow on April 14, 2008

at 3:33 pm

Congratulations should be directed to Donald Knuth, but he, apparently, does not read e-mails.

By: Alexandre Borovik on April 14, 2008

at 3:38 pm

Perhaps it’s just me, but this idea seems as though it would needless obfuscate an already difficult to grasp concept. It’s a hand waving exercise in an area where actual understanding of limits and infinitesimals is desired.

For example, what would one gain by saying sin(x) = A(1)? This is known from the definition of the sin function, but seldom in regular calculus classes does a student need to use the bounds of the function in a calculation.

As another, specifying pi = 3.14 + A(0.005) is an interesting way to approximate it’s value descriptively, but it’s necessarily imprecise. It doesn’t help the final calculations, in which case the student will use as many decimals as they see fit, or the predefined Pi variable in their calculators, and when writing equations, the symbol for pi is exact.

I can see introducing this notation and it’s concepts in a calculus course designed specifically as a mathematical primer for computer scientists, for whom it will be eventually useful, but I would have strong objection to the use of this idea in an introduction to calculus, or even forays into Real Analysis, where delta-epsilon style proofs have significant meaning which could potentially be lost by stating O(1).

Just my two cents.

By: Kevin on April 14, 2008

at 4:01 pm

It strikes me as very domain specific. Who outside of computer science majors would need it? Most other engineers and science majors don’t see it often as far as I know, and if you understand limits O(f(x)) is not hard to understand. I think if anything spend less time on limits and spend more time on an introduction to differential equations would benefit students more.

By: Kevin on April 14, 2008

at 4:55 pm

Interesting idea… but I hate it when CS folks overload the ‘=’ sign when ϵ (U+03F5 or $\in$ if it doesn’t print here) is what’s really meant. It’s much simpler to be clear about what is an element and what is a set.

By: Michael R. Head on April 14, 2008

at 5:20 pm

Wow. So that explains Calc I. Where were you three semesters ago?

@ Kevin: You make some good points; however, my guess is that teaching it this way would probably result in more people “getting it.” Those that should have an actual understanding of limits and infinitesimals (assuming that this will result in a pseudo-understanding of limits and infinitesimals) will probably be able to pick up that understanding regardless of which teaching approach is taken in the intro to Calc course.

By: Sam on April 14, 2008

at 5:25 pm

It is also easy to explain all of those other functions, like w(x), W(x), which would take, at maximum, one class of two hours exaggerating.

Note that these functions are also important, mainly when working with big field.

Thus, I approve Knuth’s idea, and I’d be happy to see a text book with this kind of fundamentals.

Breno

By: Breno Leitao on April 14, 2008

at 5:30 pm

It’s fine to tout the benefits of big-oh notation for future computer scientists who will never encounter a badly-behaved function in their lives, and who will constantly be using big-oh notation. For future mathematicians, however, the fundamental concept of limit will have far more general applicability down the road. I would have been most distressed in my later math courses had limits been left “for a more advanced course” by my intoductory calculus teacher.

It is also telling that Knuth says, “Once it is known that integration is the inverse of differentiation […]”. How would one prove the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus using big-oh notation instead of limits? I’m imagining being presented with a proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus later in my mathematical career, and thinking, “Oh, so that’s what calculus was about. Why didn’t they just tell me?”

By: Karl Juhnke on April 14, 2008

at 5:31 pm

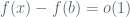

To Karl Juhnke: Here is a proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in o notation. Let and

and  continuous at

continuous at  . Then, because

. Then, because  ,

,  , that is the same as

, that is the same as  .

.

By: misha on April 14, 2008

at 6:06 pm

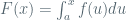

A proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus for a Lipschitz function in O notation and with the Knuth’s definition of the derivative. Let be Lipschitz, i.e.,

be Lipschitz, i.e.,  and $F(x)=\int_a^x f(u)du$.

and $F(x)=\int_a^x f(u)du$. ,

,  , and this is the same as

, and this is the same as  according to the Knuth’s definition.

according to the Knuth’s definition.

Then, because

By: misha on April 14, 2008

at 6:26 pm

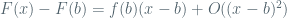

Oops! the penultimate formula in my previous comment should be:

By: misha on April 14, 2008

at 6:29 pm

To Kevin: The O notation in fact gives us the explicit instances of the epsilon-delta definitions, where delta is a function of epsilon of a specific form, instead of the claim that “for every epsilon there is delta, such that…” Let’s take a look at the O-definition of the defivative suggested by Knuth. It says that , which can be rewritten as

, which can be rewritten as  , i.e., we can take

, i.e., we can take  with some constant

with some constant  when we say that $f'(x)$ is the limit of $(f(x+h)-f(x))/h$ for

when we say that $f'(x)$ is the limit of $(f(x+h)-f(x))/h$ for  . Come to think about it, the phrase “for every epsilon there is delta” is very much the same as “delta is a function of epsilon.” This whole tradition of cramming this epsilon-delta mantra into every definition looks like a throwback to the times when the abstract notion of a function was not widely known and universally accepted yet. We can do better today. In any case, the translations between the O-definitions, explicit estimates, and epsilon-delta mantras are totally straight forward and should not cause any troubles. On the other hand, anybody who has troubles with these translations, should think twice before trying to become a mathematician, he may be not up to it.

. Come to think about it, the phrase “for every epsilon there is delta” is very much the same as “delta is a function of epsilon.” This whole tradition of cramming this epsilon-delta mantra into every definition looks like a throwback to the times when the abstract notion of a function was not widely known and universally accepted yet. We can do better today. In any case, the translations between the O-definitions, explicit estimates, and epsilon-delta mantras are totally straight forward and should not cause any troubles. On the other hand, anybody who has troubles with these translations, should think twice before trying to become a mathematician, he may be not up to it.

The O-definitions and “strong derivative” suggested by Knuth will allow exactly what you want, i.e., spending less (=zero) time on limits and spending the saved time on differential equations.

By: misha on April 14, 2008

at 7:41 pm

Is there a prize for pointing out an error in Knuth’s calculations?

In the first example, Knuth reduces A(.005) + A(0.0314) + A(.00005) to A(0.3645). I think there is a zero missing (or the decimal is misplaced); it should be A(0.03645).

By: Rob Leslie on April 14, 2008

at 7:43 pm

@Rob

There is a prize if he printed it in a book. See this wikipedia entry to try to claim your “hexadollar” check: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knuth_reward_check

By: Andrew Parker on April 14, 2008

at 8:16 pm

Using Big-O notation SERIOUSLY speeds up the process for finding divergence or convergence for series and sequences. You go from around 10 operations to 2-3 operations. Super-quick.

By: Chaos Motor on April 14, 2008

at 8:47 pm

omg yes!!! I’m doing this right now in my class

By: john on April 14, 2008

at 9:36 pm

“mathematicians customarily use the = sign as they use the word “is” in English”

News to me. I think it’s computer scientists who are careless with the = symbol. I think if this set of ideas were to be expressed without this very bad one it might be more compelling.

By: Tonio Loewald on April 14, 2008

at 10:34 pm

I like

sin(x) = A(1).

I think it would have been clarifying to me at a certain stage. While it does not confer a great deal of information about the sine function the information it does convey is definitely useful to the beginner.

To write

-1 <= sin(x) <= 1

forces the reader to digest more symbols. Symbol overload is a problem for most people in studying math. I say reduce it whenever possible.

By: Ralph on April 15, 2008

at 12:12 am

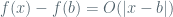

Despite of all the computational simplifications delivered by O notation, Knuth doesn’t go far enough in my opinion. He still sticks with the pointwise notion of differentiation. His constant , implicitly entering into his definition of “strong derivative at point

, implicitly entering into his definition of “strong derivative at point  ” is allowed to depend on

” is allowed to depend on  in an uncontrolled manner. When he is talking about continuity, he is still talking about pointwise continuity. It means that getting from his definitions to any practical resilts, such as the fact that a function with a positive derivative is increasing, requires a good deal of subtle reasoning that involves completeness of the reals, such as the existence of the lowest upper bound. He still would need the uniform continuity of pointwise continuous functions on a closed interval to build a definite integral, and that involves compactness, i.e., Bolzano-Weierstrass lemma and such.

in an uncontrolled manner. When he is talking about continuity, he is still talking about pointwise continuity. It means that getting from his definitions to any practical resilts, such as the fact that a function with a positive derivative is increasing, requires a good deal of subtle reasoning that involves completeness of the reals, such as the existence of the lowest upper bound. He still would need the uniform continuity of pointwise continuous functions on a closed interval to build a definite integral, and that involves compactness, i.e., Bolzano-Weierstrass lemma and such.

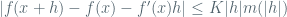

On the other hand, if we strenthen his definition of “strong differentiability” even further, by requiring the estimate

, we will end up with the derivatives that are automatically Lipschitz, and very simple proofs of the basic facts of calculus, that do not use the heavy machinery of classical analysis, such as completeness and compactness. This approach to calculus has been systematically developed. See the posting Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog.

, we will end up with the derivatives that are automatically Lipschitz, and very simple proofs of the basic facts of calculus, that do not use the heavy machinery of classical analysis, such as completeness and compactness. This approach to calculus has been systematically developed. See the posting Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog.

that is uniform in

If Lipschitz estimates are too restrictive, Holder comes to the rescue, all the proofs stay the same. Any other modulus of continuity can be used as well, and since any function, continuous on a segment has a modulus of continuity, this approach captures all the results about continuously differentiable functions. But we hardly need anything beyond Lipschitz in an undergraduate calculus course.

By: misha on April 15, 2008

at 1:37 am

Despite of all the computational simplifications delivered by O notation, Knuth doesn’t go far enough in my opinion. He still sticks with the pointwise notion of differentiation. His constant , implicitly entering into his definition of “strong derivative at point

, implicitly entering into his definition of “strong derivative at point  “, is allowed to depend on

“, is allowed to depend on  in an uncontrolled manner. When he is talking about continuity, he is still talking about pointwise continuity. It means that getting from his definitions to any practical resilts, such as the fact that a function with a positive derivative is increasing, requires a good deal of subtle reasoning that involves completeness of the reals, such as the existence of the lowest upper bound. He still would need the uniform continuity of pointwise continuous functions on a closed interval to build a definite integral, and that involves compactness, i.e., Bolzano-Weierstrass lemma and such.

in an uncontrolled manner. When he is talking about continuity, he is still talking about pointwise continuity. It means that getting from his definitions to any practical resilts, such as the fact that a function with a positive derivative is increasing, requires a good deal of subtle reasoning that involves completeness of the reals, such as the existence of the lowest upper bound. He still would need the uniform continuity of pointwise continuous functions on a closed interval to build a definite integral, and that involves compactness, i.e., Bolzano-Weierstrass lemma and such.

On the other hand, if we strenthen his definition of “strong differentiability” even further, by requiring the estimate

, we will end up with the derivatives that are automatically Lipschitz, and very simple proofs of the basic facts of calculus, that do not use the heavy machinery of classical analysis, such as completeness and compactness. This approach to calculus has been systematically developed. See the posting Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog.

, we will end up with the derivatives that are automatically Lipschitz, and very simple proofs of the basic facts of calculus, that do not use the heavy machinery of classical analysis, such as completeness and compactness. This approach to calculus has been systematically developed. See the posting Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog.

that is uniform in

If Lipschitz estimates are too restrictive, Holder comes to the rescue, all the proofs stay the same. Any other modulus of continuity can be used as well, and since any function, continuous on a segment has a modulus of continuity, this approach captures all the results about continuously differentiable functions. But we hardly need anything beyond Lipschitz in an undergraduate calculus course.

By: misha on April 15, 2008

at 3:54 am

The example “=3.14 + A(0.3645)” should be “=3.14 + A(0.03645)”.

Without this, I was looking at that example and going “huh? I don’t get it, even addition doesn’t work correctly, so how can it be called simple?” … Then I realised the example was wrong.

By: Nick J on April 15, 2008

at 4:16 am

Kevin and Karl: I don’t think the article proposes elimination of limits from the curriculum. Much less any kind of “fudging” or harmful imprecision. Rather, it discusses intermediate, yet meaningful and strictly defined, concepts. I see nothing wrong with that. Defining little-oh indeed is equivalent to defining limits, hence continuity, derivatives and integrals. Using big-oh as an important stepping stone may be worth a try.

Michael, Tonio: Look at recent publications in analysis. Big- and little-oh are used, and with the “abused” equality sign. Most of the time this is fine, as there is no possibility for confusion.

By: Arnold Layne on April 15, 2008

at 5:05 am

In my opinion Knuth doesn’t go far enough.

He still sticks with pointwise notions of differentiability and continuity that still require some heavy tools from classical analysis, such as completeness and compactness, to get any practical results. If his estimates had been uniform in x, he would have ended up with a much simpler theory, based on uniform notions and not requiring these heavy tools. See Calculus without limits in the previous reincarnation of this blog.

By: misha on April 15, 2008

at 9:37 am

I’m in Calc2 and perusing this is giving me a headache. I think I’ll stick with how I’m currently being taught :p integrating from 1 to 2 is simple enough, why throw in another layer of thinking? besides, college is easy enough these days, why allow something that simplifies it even more.

and btw I am a CS student. I know the importance of big O in CS but personally the mathematician side of me is offended to see it being “integrated” into calculus 😉

By: Michael on April 15, 2008

at 1:02 pm

To misha: I don’t see how you can control your error term in your proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus without unpacking the definition of integration. Come to think of it, integration wasn’t defined at all in Knuth’s letter. Maybe he just didn’t have time. Instead of jumping ahead to wonder how the big theorem was proved with big-oh notation and without limits, I should have first asked how integration was defined with big-oh notation and without limits. Perhaps with that answer under my belt it would all become clear to me.

By: Karl Juhnke on April 16, 2008

at 3:55 pm

On further consideration, perhaps the magic is not in the notation at all, but rather in assuming all functions are sufficiently well-behaved so that the notation is adequate? I can see a strong case for teaching “Calculus of Friendly Functions” to the majority of people who study calculus. For me, however, real analysis was full of intuition-breaking functions that forced me to go back to the definitions. It seems that having some practice with limits prior to real analysis helped me get in synch with all the mind-bending concepts, whereas had I been taught calculus with big-oh notation, my intuition would be under-developed. Are fans of Knuth’s proposal suggesting it is better for mathematicians as well as for computer scientists?

By: Karl Juhnke on April 16, 2008

at 4:45 pm

Lipschitz function — got it now.

By: Karl Juhnke on April 16, 2008

at 4:50 pm

To Karl Juhnke: Look, I’m not entirely against continuity, limits, pointwise differentiability and such. I’m just against starting with them. If you make the estimate in Knuth’s strong derivative definition uniform in , you will end up with calculus of Lipschitz functions. Scroll down to Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog for details. A lot of the intuition-breaking functions are artifacts of the weak “classical” definitions and are irrelevant in the vast majority of applications. Also “Calculus of Friendly Functions” can be a good stepping stone to the classical analysis even for math majors, who will have learn about Lipschitz functions and moduli of continuity anyway.

, you will end up with calculus of Lipschitz functions. Scroll down to Calculus without limits on the previous reincarnation of this blog for details. A lot of the intuition-breaking functions are artifacts of the weak “classical” definitions and are irrelevant in the vast majority of applications. Also “Calculus of Friendly Functions” can be a good stepping stone to the classical analysis even for math majors, who will have learn about Lipschitz functions and moduli of continuity anyway.

By: misha on April 16, 2008

at 7:41 pm

Karl Juhnke said:

I can see a strong case for teaching “Calculus of Friendly Functions” to the majority of people who study calculus.

I cannot agree more. The only issue is elementary definition of an appropriate class of functions.

By the way, there is a a well-developed theory of “o-minimal structures”, part of model theory, where every definable function (that is, “friendly” function) has a wonderful property: it is piecewise monotonous-and-taking-all-intermediate-values). Unfortunately, it is difficult to deal with general monotonous-and-taking-all-intermediate-values functions – they are continuous (and, moreover, obviously so — these are archetypal continuous functions, fitting into our intuition of continuity), but the class is not closed under addition. Finding a narrower explicitly and elementary defined subclass with good natural properties is an interesting problem — but it is unclear even whether it has a solution.

The theory of o-minimal structures originates in a classical work by Alfred Tarski on decision procedure for Euclidean geometry.

By: Alexandre Borovik on April 17, 2008

at 6:16 am

Coming back to calculus, we actually can define an increasing function on an inreval to be continuous if it doesn’t skip any values, and then we can define a fanction to be continuous at

to be continuous at  if there is an increasing continuous function

if there is an increasing continuous function  , defined for

, defined for  , such that

, such that  and

and  . This is the way it is done in a ground-breaking book “An Infinite Series Approach to Calculus” by Susan Bassein (Publish or Perish, 1993), page 67. A short note on continuity I wrote a while ago, especially exercises 3 to 8, may clarify the matter (since then I have abandoned continuity in favor of explicit uniform estimates).

. This is the way it is done in a ground-breaking book “An Infinite Series Approach to Calculus” by Susan Bassein (Publish or Perish, 1993), page 67. A short note on continuity I wrote a while ago, especially exercises 3 to 8, may clarify the matter (since then I have abandoned continuity in favor of explicit uniform estimates).

Now, the class of increasing continuous functions is closed under addition

(and multiplication by positive constants), it provides an adequate tool to develop the o-notation systematically.

Pushing this approach a bit further by requiring the estimate on to be uniform in both

to be uniform in both  and

and  , we arrive naturally at “Calculus without limits” from the previous reincarnation of this blog.

, we arrive naturally at “Calculus without limits” from the previous reincarnation of this blog.

Since any continuous function on a closed interval has a global modulus of continuity, all the continuous functions become “friendly functions,” and we can look at differentiation as division of by

by  in the ring of friendly functions. Of course, it is natural to start with polynomials and then move to Lipschitz and maybe Holder functions as “friendly,” before exploring the general continuity. This is the approach that I love.

in the ring of friendly functions. Of course, it is natural to start with polynomials and then move to Lipschitz and maybe Holder functions as “friendly,” before exploring the general continuity. This is the approach that I love.

By: misha on April 17, 2008

at 9:20 am

With all apologies to Knuth (and a lot of reverence) …

I’m not a mathematician, but I tutored a lot of calculus to reluctant business majors to make ends meet in college. When I tried to get a student to understand what calculus “is” I often found Leibniz’s notation to be superior to Lagrangian notation. It stresses, simply and visually, the fact that we’re talking about slope when we’re talking about derivatives.

While this notation looks like fun for CS majors (as noted above) it also appears like it gets away from what is fundamentally being emphasized: just take the slope.

Add in the confusion of saying “=” no longer denotes transitive equality and you might have a bigger mess than the one you started with.

By: b8sell on April 17, 2008

at 8:20 pm

I’m a big Knuth fan, but the thought of teaching calculus this way gives me a combination of a headache and fits of laughter. Some of my calculus students cannot remember how to add integer fractions, cannot solve 3x+2=0, and want to use the Product Rule to differentiate ln(x) (because it’s “ln” times x). Something tells me Knuth wasn’t entirely serious in pushing this as a “calculus reform” effort.

By: Robert on April 18, 2008

at 1:45 am

Alexandre,

I realize this may come across as nitpicking, but I’m not sure I’d agree that the theory of o-minimal structures originates in the Tarski-Seidenberg theorem. Certainly that work, and particularly their method of quantifier elimination, has been a source of inspiration for many, but the result is restricted to just one particular structure: that of semi-algebraic sets (sets which are definable by means of polynomial inequalities).

My understanding is that only later did it dawn on model theorists that the o-minimality condition on a general structure had such powerful consequences — and due to a paucity of examples (the main one being Tarski’s), the subject didn’t really take off until Wilkie came out with his remarkable result, that the expansion of semi-algebraic sets that results by adding an exponential function is o-minimal. You may be more expert than I in this area, but I’d be more inclined to say that the theory really originates in those two developments, even conceding that Tarski-Seidenberg has always played an archetypal role.

You can do a lot of fun calculus (from the big O point of view) with Wilkie’s structure and further expansions, but the uncomfortable fact remains that with o-minimality, you can never incorporate the sine function in this setting. Is this something that Shiota’s X-sets can handle?

By: Todd Trimble on April 18, 2008

at 1:45 am

Pushing Knuth’s idea to its limit, take any modulus of continuity, i.e. a convex increasing function , defined for

, defined for  ,

,  and not skipping any values (i.e., continuous at 0, continuity for strictly positive

and not skipping any values (i.e., continuous at 0, continuity for strictly positive  being automatic). Then Knuth’s “strong derivative” concept with

being automatic). Then Knuth’s “strong derivative” concept with  replaced by

replaced by  and

and  uniform in

uniform in  , will give you calculus without limits.

, will give you calculus without limits.

By: misha on April 19, 2008

at 3:36 am

It should have been … replaced by

replaced by  “… in comment 30, sorry for messing up.

“… in comment 30, sorry for messing up.

To Robert: you remark only indicates that any “calculus reform” will not work without a reform of the rest of mathematical education.

By: misha on April 19, 2008

at 3:49 am

Todd Trimble said:

You can do a lot of fun calculus (from the big O point of view) with Wilkie’s structure and further expansions, but the uncomfortable fact remains that with o-minimality, you can never incorporate the sine function in this setting. Is this something that Shiota’s X-sets can handle?

Yes, Shiota’s universe looks like a good idea. But in any case, a lot of serious mathematical work will be needed before a reasonable concept of “friendly functions” is born.

By: Alexandre Borovik on April 19, 2008

at 6:19 pm

I claim that Calculus of Friendly Functions is already here for everybody to enjoy. Here is how. Take you favorite modulus of continuity , then uniform

, then uniform  -differentiability can be defined by the inequality

-differentiability can be defined by the inequality

uniform in

uniform in  .

. -continuous, i.e., it will satisfy the inequality

-continuous, i.e., it will satisfy the inequality  uniform in

uniform in  . Any

. Any  -continuous function

-continuous function  has a primitive

has a primitive  that is uniformly

that is uniformly  -differentiable. All the proofs are clean and simple, on the level of hight school algebra. How can it be friendlier?

-differentiable. All the proofs are clean and simple, on the level of hight school algebra. How can it be friendlier?

The derivative will be uniformly

By: misha on April 19, 2008

at 7:39 pm

Misha: My dream is to get rid of inequalities and work with piecewise monotonous-and-taking-all-intermediate-values functions. This is a class of functions sufficient for doing most of mathematical economics (but not models of derivatives trading, I have to admit — but perhaps derivatives trading will eventually be outlawed).

By: Alexandre Borovik on April 19, 2008

at 7:48 pm

To Alexandre: I must admit that getting rid of inequaities looks a bit too radical to me. What is left then? Aren’t inequalities implicitly present in O and o notations and semi-algebraic and semi-amalytic sets? What kind of problems in mathematical economics can be treated, or you would like to treat, without inequalities? Can you give a reference maybe? It’s probably a topic for another posting, since you and Todd clearly went off on a tangent here. I’m not sure whether complete formalization and axiomatization of O and o notations will help make calculus more widely understandable.

By: misha on April 20, 2008

at 1:25 am

Misha, the “tangent” where I was a commenter was about friendly functions, where you were a participant as well. Alexandre was pointing out o-minimal structures as giving classes of friendly functions, but part of my point (and his too) was that these classes may not be general enough.

The “o” stands for “order”, that is the binary relation < which is assumed to be part of the structure we are considering — the theory of o-minimal structures is therefore in the direction opposite to getting rid of inequalities. (“O-minimal” means that the only subsets of which are definable in the structure are the ones already guaranteed to be in the structure: finite unions of points and intervals. The book by van den Dries, Tame Topology and O-minimal Structures, is a very good introduction — the word “tame” meaning friendly in the sense of being free of pathology; cf. Grothendieck’s Esquisse d’un Programme.)

which are definable in the structure are the ones already guaranteed to be in the structure: finite unions of points and intervals. The book by van den Dries, Tame Topology and O-minimal Structures, is a very good introduction — the word “tame” meaning friendly in the sense of being free of pathology; cf. Grothendieck’s Esquisse d’un Programme.)

By: Todd Trimble on April 20, 2008

at 12:05 pm

Thanks for the explanations and the references, Todd. As for the tension between friendliness as the absence of pathologies (or amenability to explicit or numerical calculations) and generality of our axioms, I think it will always be with us. How to resolve this tension of course depends on the problem that the theory is applied to. My attitude is that theories are mostly the means to the ends (of solving problems), not the ends in themselves.

By: misha on April 20, 2008

at 4:52 pm

I can not resist quoting the concluding remarks of the presidential address to the London Mathematical Society by Michael Atiyah (Bull. London Math. Soc., 10, 1978, 69-76), called “The Unity of Mathematics,” that still ring true today, maybe even more so than in 1976:

By: misha on April 21, 2008

at 3:15 am

To Alexandre: you can “get rid of inequalities” in differentiation, by viewing differentiation as division in your favorite class of (globally defined) “friendly” functions (uniformly continuous functions will do). This will work for many variables as well, because you have to divide by polynomials only, and polynomials can vanish only on sets without any interior points. I tried to explain it elsewhere, but encountered some misunderstanding and resistance. So you can look at differentiation as a purely algebraic matter. But still inequalities sneak in through the back door, so to speak, because you have to describe your friendly functions, and some restrictions on the variation in terms of inequalities will be necessary (you have mentioned monotonicity, for example). Also at some point you will have to explain why tangents look like tangents, why they cling to the graphs, and you will need inequalities again to explain the very meaning of differentiation as linear approximation.

in terms of inequalities will be necessary (you have mentioned monotonicity, for example). Also at some point you will have to explain why tangents look like tangents, why they cling to the graphs, and you will need inequalities again to explain the very meaning of differentiation as linear approximation.

A correction: In comment #30, line 2, it should be concave, not convex.

By: misha on April 21, 2008

at 4:46 pm

Robert wrote: I’m a big Knuth fan, but the thought of teaching calculus this way gives me a combination of a headache and fits of laughter. Some of my calculus students cannot remember how to add integer fractions, cannot solve 3x+2=0, and want to use the Product Rule to differentiate ln(x) (because it’s “ln” times x).

That is the most ridiculous thing. Why are these students even taking calculus? They should be taking remedial math.

By: Al Bumen on February 24, 2009

at 7:16 pm

I have a moved my web page to http://www.mathfoolery.com a couple of days ago, sorry for any inconvenience. Also my article not quite finished article at http://arxiv.org/abs/0905.3611 may be of interest

By: misha on September 5, 2009

at 6:22 am

i have some problem to understand tho big-o notation i need help to the function in maths practice ?

By: younous on October 30, 2009

at 7:21 am

Some of calculus can be done on discrete structures, without limits. That would greatly speed up a course.

This approach could be used for example to tell a group of normal, non-mathematical adults what a derivative is. Gilbert Strang got the basic picture down to 40 minutes here: http://ocw.mit.edu/resources/res-18-005-highlights-of-calculus-spring-2010/highlights_of_calculus/big-picture-of-calculus/ but I think you could explain a derivative is in 10 minutes, with computer graphics, pre-loaded data (for example http://media.tumblr.com/4567487c802ce60df944785c233cb5eb/tumblr_inline_mkgbvtq2351qbdydv.png + http://media.tumblr.com/3c6ff79662a5b628e55b86c39c0675f1/tumblr_inline_mkgax5A89h1qbdydv.png), `lag`/`diff`, and “overloaded” Cartesian pictures like this: http://media.tumblr.com/cf27f5a7d9d28700c7c329f600bcd375/tumblr_inline_mf8tm1KZkY1qbdydv.png + http://media.tumblr.com/1ac8510bcd509ac915da70e72d375dfa/tumblr_inline_mf8t98qfo11qbdydv.png + http://media.tumblr.com/7b578ae7121a9eedd86c7f1fd92385b9/tumblr_inline_mf8rimE0T81qbdydv.png. (Strang does essentially this in one of his lectures: comment that `square − lag( square ) = double`, say “Hmm…” and leave it there for contemplation.)

Or you could quickly show undergraduates a baby version of Green’s theorem on a 1-simplex, again in under 10 minutes.

By: isomorphismes on March 18, 2015

at 6:08 pm

wh0cd439775 zithromax

By: Stewarttiese on August 30, 2017

at 3:13 am

I found this letter while searching for information about defining differentiation in terms of big-O notation. Very illuminating!

By: Rob on April 27, 2018

at 9:54 am

Maybe the open-source community is able to produce this book?

https://github.com/Alex-Linhares/Knuths-O-Calculus/blob/master/README.md

By: Alexandre Linhares on August 24, 2018

at 8:58 pm